State versus local government power to regulate environmental problems in NC

In late March 2016, North Carolina took front stage in national political news. The legislature convened for a one-day special session to pass a bill preventing local governments from enacting anti-discrimination ordinances. Some of the news coverage, national and state, addressed the general issue of the legislature’s stripping power away from local governments in other areas, notably local government structure, taxing authority and infrastructure ownership.

Over the past five years, the North Carolina legislature has also stripped the state’s local governments of many of their powers to regulate environmental threats. This trend has not been widely reported. In this entry I will catalog some of the recent changes in local government’s environmental regulatory powers–all of them reductions in such powers.

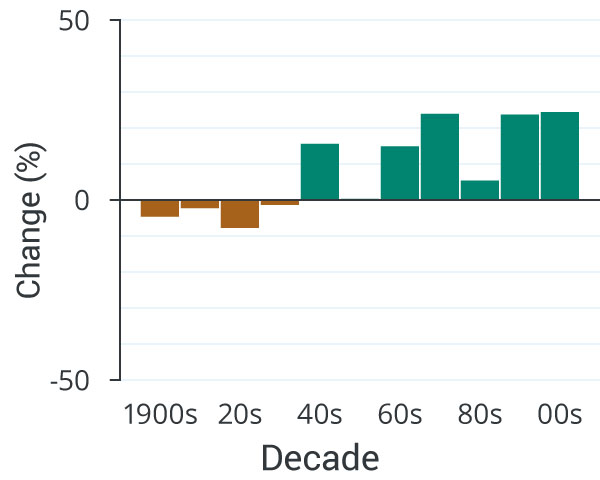

These changes also should be viewed in a longer historical context, however. There has been dynamic ebb and flow between local governments, the State, and the federal government in power to regulate the environment ever since the passage in the 1970s and 1980s of the nation’s major federal environmental statutes. This entry will also go back to the start of the State of North Carolina and describe what I see as five major periods with different arrangements of local versus State environmental regulatory power:

- A Preindustrial era of purely local control (1700s to 1900)

- Early industrial era of State floors with local flexibility (1900 to 1970)

- Late industrial era of federal mandates with potential State flexibility, limited in NC by the legislature (1970 to 1990)

- Postindustrial era of federal and State “devolution” of power, yielding many localized or “place-based regulations” (1990s to 2010)

- Great Recession and post-recession era clampdown on agency and local environmental discretion (2011 to present)

An important feature of all this ebb and flow is that new eras never completely wiped out the programs and laws created in early eras. The power swished around like water beneath coastal piers, but the old programs often remained, like barnacles, some alive and others just crusty hulks of their former living selves. I will start with the recent era and work backwards in time. Some of the most interesting legal problems are presented by the persistence of those earliest barnacles.

Read More →